Etat français et collaboration

![]()

Le 26 juin 1940, au lendemain de l’entrée en vigueur des armistices, Pétain annonce qu’ « un ordre nouveau commence ». Le 10 juillet, le Parlement lui vote les pleins pouvoirs et le lendemain, la IIIe République meurt pour faire place à l’État français. Très vite arrivent les premières mesures établissant cet « ordre nouveau » : la création de la Légion française des combattants, les internements administratifs, le statut des Juifs, le remplacement des Conseils généraux par une commission administrative nommée… La poignée de mains de Montoire-sur-le-Loir, le 24 octobre 1940, symbolise la « collaboration », qui sera officiellement annoncée par Pétain une semaine après. La création des structures nécessaires à cette politique intervient rapidement.

![]() French State and Collaboration

French State and Collaboration

June 26th, 1940, the very next day after the armistices come into force, Petain announces that a "new order is beginning". July 10th, Parliament votes him into full power, and the next day, the Third Republic dies to make way for the French State. The first measures establishing this "new order" arrive very quickly: the creation of the French Legion of combatants, administrative detentions, the status of Jews, the replacement of General Councils by an administrative panel appointed...The Montoire handshake, on October 24th, 1940, symbolises the "collaboration" which will be officially announced by Petain a week later. The creation of structures necessary for this policy comes quickly.

Traduction : Megan Berman

Dvd-rom La Résistance dans la Drôme-Vercors, éditions AERI-AERD, février 2007.

Plan de l'expo

La Résistance en Drôme-Vercors

1. Zone "libre" et occupations

1.1 Chronologie de la Drôme

1.1.1 Juin 1940 : arrivée des Allemands dans la Drôme

1.1.2 Juin 1940 - 11 novembre 1942 : la Drôme en zone non occupée

1.1.3 11 nov. 1942 - 9 sept. 1943 : la Drôme sous occupation italienne

1.1.4 9 sept. 1943 - 31 août 1944 : la Drôme sous occupation allemande

1.2 Etat français et collaboration

1.2.1 Organisation administrative sous Vichy

1.2.2 Camps drômois pour Indésirables

1.2.3 Organisations et partis de l'État de Vichy

1.2.4 Relève et STO

1.2.5 Fêtes du Maréchal

1.3 Oppression et censure

1.3.1 Presse et radio officielles

1.3.2 Restrictions et contraintes

1.3.3 Propagande et censure

1.3.4 Mesures de surveillance et contrôle

1.4 Persécutions antisémites

1.4.1 Les Juifs installés, réfugiés ou incarcérés dans la Drôme

1.4.2 Législation antijuive

1.4.3 Rafles et arrestations de Juifs, la déportation

1.4.4 Cache et sauvetage des Juifs

1.5 Répression avant le 6 juin 1944

1.5.1 Vichy met en place son système répressif

1.5.2 Internement : les prisons

1.5.3 Massacres

1.5.4 Déportation et répression

2. Résistance

2.1 Motivations

2.1.1 Entrer en Résistance

2.1.2 Formation

2.2 Ecrits clandestins

2.2.1 Tracts, graffitis, papillons

2.2.2 Journaux de la Résistance, imprimeries clandestines

2.3 Grèves et manifestations

2.3.1 Dans les usines

2.3.2 Contre la pénurie

2.3.3 Contre le STO

2.3.4 Dates ou lieux symboliques

2.4 Organisations

2.4.1 Liaisons

2.4.2 Service de santé

2.4.3 Mouvements de Résistance

2.4.4 Différents réseaux agissant dans la Drôme

2.4.5 Maquis : de la planque de réfractaires aux camps de maquisards

2.5 Vivre en Résistance

2.5.1 Soutien de la population

2.5.2 Planques

2.5.3 Faux papiers

2.5.4 Résister en chantant

2.6 Sociologie des résistants

2.6.1 Femmes dans la Résistance

2.6.2 Jeunes dans la Résistance

2.6.3 Etrangers dans la Résistance

2.6.4 Intellectuels dans la Résistance

2.6.5 Religion et Résistance

2.6.6 Quelques figures de la Résistance drômoise

2.6.7 Drômois ayant des responsabilités hors du département

2.7 La lutte

2.7.1 Coups de main

2.7.2 Sabotages ferroviaires

2.7.3 Sabotages divers

2.7.4 Attentats contre les collaborateurs et leurs locaux

2.7.5 Attentats contre les occupants et leurs locaux, cinémas

2.7.6 Corps-franc Paul Bernard

2.8 Liaisons entre les Alliés et la France libre

2.8.1 Écoute des radios interdites

2.8.2 BCRA, SAP, OSS, SOE

2.8.3 Renseignement et liaisons radio

2.8.4 Parachutages et atterrissages, l'armement de la Résistance

2.9 S'unir et reconstruire

2.9.1 AS et FTP : rapports difficiles, coordination

2.9.2 Partis et syndicats aux côtés de la Résistance

2.9.3 Formation clandestine des CDL et CLL

2.9.4 Unification des unités militaires résistantes

2.10 Projet Vercors (avant le 6 juin 1944)

2.10.1 Présentation géographique du Vercors

2.10.2 Organisation

2.10.3 Premiers accrochages

3. Libération et après-libération dans la Drôme

3.1 Après le 6 juin 1944

3.1.1 Résistance au grand jour, la montée au Vercors

3.1.2 Premiers combats : Crest, Etoile, Saint-Rambert...

3.1.3 Combats en centre Drôme

3.1.4 Combats dans le sud de la Drôme

3.1.5 Débandade de la Milice, une gendarmerie avec la Résistance

3.1.6 Bombardements alliés meurtriers

3.1.7 Premières libérations dans la Drôme

3.2 Assaut allemand sur le Vercors

3.2.1 Freiner les Allemands dans leur assaut du Vercors

3.2.2 Les « Mongols » sèment la terreur à Crest

3.2.3 Assaut allemand du 21 juillet 1944 contre le Vercors

3.2.4 La terreur dans le Vercors

3.2.5 Combats sur les bordures du Vercors

3.3 Bombardements, massacres, déportations (6 juin à fin août 1944)

3.3.1 Bombardements allemands

3.3.2 Massacres allemands pendant l'été 1944

3.3.3 Déportations en juin-juillet 1944

3.4 Arrivée des Alliés

3.4.1 Vie d'une compagnie de résistants drômois

3.4.2 Du débarquement en Provence à la retraite allemande

3.4.3 Bataille de Montélimar

3.5 Libération des villes et des villages

3.5.1 Montélimar

3.5.2 Libération de Romans-sur-Isère et Bourg-de-Péage

3.5.3 Libération de Valence

3.5.4 Libération d’autres villes et villages

3.6 Après libération

3.6.1 La liesse de la Libération

3.6.2 Mise en place des nouveaux pouvoirs

3.6.3 Prisonniers de guerre (PG) allemands

3.6.4 Epuration

3.6.5 Résistants dans la nouvelle situation politique

3.6.6 Reprise de la vie économique et reconstruction

3.6.7 Intégration des résistants dans l'armée régulière

3.6.8 Retour des absents

4. Mémoire

4.1 Lieux de mémoire

4.1.1 Vassieux-en-Vercors

4.1.2 La Chapelle-en-Vercors

4.1.3 Hôpital du maquis (Saint-Martin-en-Vercors / La Luire)

4.1.4 Monuments aux morts communaux

4.1.5 Autres monuments

4.1.6 Musées de la Résistance de la Drôme

4.1.7 Mémoriaux

4.1.8 Nécropole et cimetière national

4.1.9 Traces, plaques et stèles

4.1.10 Lieux de culte

4.2 Cérémonies et commémorations

4.2.1 Commémorations au lendemain de la guerre

4.2.2 Cérémonies individuelles ou familiales

4.2.3 Commémorations officielles

4.2.4 Cérémonies particulières

4.3 Acteurs de la mémoire

4.3.1 Associations d’anciens résistants et déportés

4.3.2 La Résistance transmise aux jeunes

4.3.3 Chemins des lieux de mémoire

4.3.4 Oeuvres artistiques et intellectuelles

Crédits

Crédits

CONCEPTION, RÉALISATION

Maîtres d’ouvrage : Association pour l’Élaboration d’un Cédérom sur la Résistance dans la Drôme (AERD), en lien avec l'Association pour des Études sur la Résistance intérieure (AERI) au niveau national.

Maîtrise d’ouvrage : Carré multimédia.

Gestion de projet AERI : Laurence Thibault (directrice) – Laure Bougon (chef de projet) assistée d’Aurélie Pol et de Fabrice Bourrée.

Groupe de travail : Pierre Balliot, Alain Coustaury, Albert Fié, Jean Sauvageon, Robert Serre, Claude Seyve, Michel Seyve. Patrick Martin et Gilles Vergnon interviennent sur des notices spécifiques.

Sont associés à ce travail tous ceux qui ont participé à la réalisation du Dvd-rom La Résistance dans la Drôme, et qui par la même, ont contribué à une meilleure connaissance de la Résistance dans le département.

Groupe pédagogique : Patrick Dorme (CDDP Drôme), Lionel FERRIERE (enseignant Histoire en collège et correspondant du musée de Romans), Michel MAZET (enseignant en lycée et correspondant des archives départementales).

Cartographie : Christophe Clavel et Alain Coustaury.

Partenaires

Partenaires

Ce travail n’aurait pu avoir lieu sans l’aide financière du Conseil général de la Drôme, du Conseil régional de Rhône-Alpes, du Groupe de Recherches, d’Études et de Publications sur l’Histoire de la Drôme (GRÉPHiD) et de l'AERD qui y a affecté une partie des recettes de la vente des dvd-roms, La Résistance dans la Drôme et le Vercors.

L’équipe de la Drôme tient à les remercier ainsi que :

- l’Office départemental des anciens combattants (ONAC),

- la Direction départementale de l’équipement de la Drôme (DDE),

- le Centre départemental de documentation pédagogique de la Drôme, (CDDP),

- le personnel et la direction des Archives départementales de la Drôme, de l’Isère, des Archives communales de Allan, de Crest, de Die, de Grâne, de Montélimar, de Romans-sur-Isère, de Triors, de Saint-Donat-sur-l’Herbasse, de Saint-Uze,

- les Archives fédérales allemandes (Bundesarchiv), le National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), The National Archives (les archives nationales britanniques), Yad Vashem,

- le Musée de la Résistance en Drôme et de la Déportation de Romans, le Musée de la Résistance de Vassieux-en-Vercors, le Mémorial de La Chau, le Musée de Die, le Musée Saint-Vallier, la Médiathèque de Montélimar, le Musée de la Résistance et de la Déportation de l’Isère, le Mémorial Shoah, l’Association des Amis du Musée des blindés de Saumur, le Musée de la Division Texas (USA),

- l’Association Études drômoises, l’Association Mémoire d’Allex, l’Association Sauvegarde du Patrimoine romanais-péageois, l’Association Mémoire de la Drôme, l’Association des Amis d’Emmanuel Mounier, l’Association Patrimoine, Mémoire, Histoire du Pays de Dieulefit, l’Amicale maquis Morvan, la Fédération des Unités Combattantes et des FFI de la Drôme, l’Association nationale des Pionniers et Combattants Volontaires du Vercors.

Mais nos remerciements s’adressent surtout à toutes celles et tous ceux, notamment résistantes, résistants et leurs familles, qui ont accepté de livrer leurs témoignages, de nous confier leurs documents et leurs photographies. Ils sont très nombreux et leurs noms figurent dans cette exposition. Ils s’apercevront au fil de la lecture que leur contribution a été essentielle pour l’équipe qui a travaillé à cette réalisation. Grâce à eux, une documentation inédite a pu être exploitée, permettant la mise en valeur de personnes, d’organisations et de faits jusqu’alors méconnus. Grâce à eux nous avons pu avancer dans la connaissance de la Résistance dans la Drôme et plus largement dans celle d’une histoire de la Drôme sous l’Occupation.

L’étude de cette période et des valeurs portées par la Résistance, liberté, solidarité, justice et progrès social…, nous semble plus que jamais d’actualité.

Bibliographie

Bibliographie

Publications locales :

Une bibliographie plus détaillée sera accessible dans l’espace « Salle de consultation » du Musée virtuel.

SAUGER Alain, La Drôme, les Drômois et leur département. 1790-1990. La Mirandole. 1995.

GIRAUDIER Vincent, MAURAN Hervé, SAUVAGEON Jean, SERRE Robert, Des Indésirables, les camps d’internement et de travail dans l’Ardèche et la Drôme durant la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Peuple Libre et Notre Temps, Valence, 1999.

FÉDÉRATION DES UNITÉS COMBATTANTES DE LA RÉSISTANCE ET DES FFI DE LA DRÔME, Pour l’amour de la France. Drôme-Vercors. 1940-1944. Peuple Libre, Valence, 1989.

DE LASSUS SAINT-GENIÈS (général), DE SAINT-PRIX, Combats pour le Vercors et la Liberté. Peuple Libre, Valence, 1982.

LA PICIRELLA Joseph. Témoignages sur le Vercors, 14e édition, Lyon, 1994

LADET René, Ils ont refusé de subir. La Résistance en Drôme. Auto-édition. Portes-lès-Valence, 1987.

DREYFUS Paul, Vercors, citadelle de Liberté, Arthaud, Grenoble, 1969.

MARTIN Patrick, La Résistance dans le département de la Drôme, Paris IV Sorbonne, 2002.

SERRE Robert, De la Drôme aux camps de la mort, Peuple Libre et Notre Temps, Valence, 2006.

SUCHON Sandrine, Résistance et Liberté. Dieulefit 1940-1944. Éditions A Die. 1994.

VERGNON Gilles, Le Vercors, histoire et mémoire d’un maquis, L’Atelier, Paris, 2002.

Dvd-rom La Résistance dans la Drôme et le Vercors, éditions AERD-AERI, 2007.

Cartographie

Cartographie

Il s'agit d'une sélection de cartes nationales et locales sur la Résistance. La plupart de ces cartes ont été réalisées par Christophe Clavel et Alain Coustaury. Il s'agit d'une co-édition AERI-AERD tous (droits réservés)

France de 1940 à 1944

France de 1940 à 1944 Départements français sous l’Occupation

Départements français sous l’Occupation Régions militaires de la Résistance en 1943

Régions militaires de la Résistance en 1943 La Drôme, géographie physique

La Drôme, géographie physique Esquisse de découpage régional de la Drôme

Esquisse de découpage régional de la Drôme Les communes de la Drôme

Les communes de la Drôme Carte des transports en 1939

Carte des transports en 1939 Le confluent de la Drôme et du Rhône

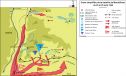

Le confluent de la Drôme et du Rhône Densité de la population de la Drôme en 1939

Densité de la population de la Drôme en 1939 Densité de la population de la Drôme en 1999

Densité de la population de la Drôme en 1999 Evolution de la densité de population de la Drôme entre 1939-1999

Evolution de la densité de population de la Drôme entre 1939-1999 L’aérodrome de Montélimar-Ancône

L’aérodrome de Montélimar-Ancône Aérodrome de Valence - Chabeuil - La Trésorerie

Aérodrome de Valence - Chabeuil - La Trésorerie Les caches des armes et du matériel militaire

Les caches des armes et du matériel militaire Les terrains de parachutages dans la Drôme

Les terrains de parachutages dans la Drôme Bombardements alliés et allemands dans la Drôme

Bombardements alliés et allemands dans la Drôme Immeubles détruits par les Allemands et la Milice

Immeubles détruits par les Allemands et la Milice Emplacement de camps de maquis de 1943 au 5 juin 1944

Emplacement de camps de maquis de 1943 au 5 juin 1944 Localisation des groupes francs qui ont effectué des sabotages en 1943

Localisation des groupes francs qui ont effectué des sabotages en 1943 Implantation et actions de la compagnie Pons

Implantation et actions de la compagnie Pons FFI morts au combat ou fusillés

FFI morts au combat ou fusillés Plan-de-Baix, Anse, 16 avril 1944

Plan-de-Baix, Anse, 16 avril 1944 Géopolitique de la Résistance drômoise en juin-juillet 1944

Géopolitique de la Résistance drômoise en juin-juillet 1944 Dispositif des zones Nord, Centre, Sud vers le 10 juin 1944

Dispositif des zones Nord, Centre, Sud vers le 10 juin 1944 Combovin, 22 juin 1944

Combovin, 22 juin 1944 Vassieux-en-Vercors 21, 22, 23 juillet 1944

Vassieux-en-Vercors 21, 22, 23 juillet 1944 Combat de Gigors 27 juillet 1944

Combat de Gigors 27 juillet 1944 Le sabotage du pont de Livron

Le sabotage du pont de Livron Carte simplifiée de la bataille de Montélimar du 21 au 24 août 1944

Carte simplifiée de la bataille de Montélimar du 21 au 24 août 1944 Carte simplifiée de la bataille de Montélimar du 25 et 26 août 1944

Carte simplifiée de la bataille de Montélimar du 25 et 26 août 1944 Carte simplifiée de la bataille de Montélimar du 27 au 29 août 1944

Carte simplifiée de la bataille de Montélimar du 27 au 29 août 1944 Carte simplifiée de la bataille de Montélimar du 29 août à 12 heures le 30 août 1944

Carte simplifiée de la bataille de Montélimar du 29 août à 12 heures le 30 août 1944 Etrangers au département, non juifs, arrêtés dans la Drôme et déportés

Etrangers au département, non juifs, arrêtés dans la Drôme et déportés Déportation, arrestations dans la Drôme

Déportation, arrestations dans la Drôme Déportation des Juifs dans la Drôme

Déportation des Juifs dans la Drôme Lieu de naissance de Drômois déportés, arrêtés dans la Drôme et à l’extérieur du département

Lieu de naissance de Drômois déportés, arrêtés dans la Drôme et à l’extérieur du département Cartes des principaux lieux de mémoire dans la Drôme

Cartes des principaux lieux de mémoire dans la Drôme Perceptions de la Résistance drômoise

Perceptions de la Résistance drômoiseChronologie

Chronologie

1. De la déclaration de guerre à l’Armistice, le 22 juin 1940 : Un mois après le début de leur attaque en mai 1940, les Allemands atteignent le nord de la Drôme. L’Armistice arrête les combats sur la rivière Isère. Le nord du département est occupé par les troupes allemandes.

2. De l’Armistice à l’occupation allemande, le 11 novembre 1942 : La Drôme est située en zone non occupée.

3. Du 11 novembre 1942 au 9 septembre 1943 : La Drôme est placée sous administration et occupation italiennes.

4. Du 9 septembre 1943 au 31 août 1944 : l’armée allemande occupe la Drôme ; c’est la période la plus intense pour la lutte contre l’ennemi et le gouvernement de Vichy.

Frise chronologique

Frise chronologiquePédagogie

Pédagogie

ESPACE PEDAGOGIQUE

Objectif de cet espace : permettre aux enseignants d\'aborder plus aisément, avec leurs élèves, l\'exposition virtuelle sur la Résistance dans la Drôme en accompagnant leurs recherches et en proposant des outils d’analyse et de compréhension des contenus.

L'espace d'exposition s'articule autour d'une arborescence à quatre entrées :

- Zone libre et Occupation,

- Résistance,

- Libération et après-libération,

- Mémoire.

Chaque thème est introduit par un texte contextuel court. A partir de là, des documents de tous types (papier, carte, objet, son, film) sont présentés avec leur notice explicative.

La base média peut être aussi utilisée comme ressource pour les enseignants et leurs élèves dans le cadre de travaux collectifs ou individuels, en classe ou à la maison.

Pour l'exposition sur la Résistance dans la Drôme, sont proposés aux enseignants des parcours pédagogiques (collège et lycée), en lien avec les programmes scolaires, utilisant les ressources de l'exposition :

1/ Collège :

- Note méthodologique

- Parcours pédagogiques composés de :

. Fiche 1 : La France vaincue, occupée et libérée,

. Fiche 2 : Le gouvernement de Vichy, la Révolution nationale et la Collaboration,

. Fiche 3 : Vivre en France durant l'Occupation,

. Fiche 4 : La Résistance.

2/ Lycée :

- Note méthodologique

- Parcours pédagogiques composés de :

. Dossier 1 : L'Etat français (le régime de Vichy),

. Dossier 2 : Les Juifs dans la Drôme (antisémitisme, persécution, arrestation, déportation, protection),

. Dossier 3 : Les résistants,

. Dossier 4 : La Résistance armée,

. Dossier 5 : La Résistance non armée,

. Dossier 6 : La vie quotidienne.

Si vous êtes intéressés par ces dossiers, contactez nous : [email protected]

Réalisation des dossiers pédagogiques : Patrick Dorme (CDDP Drôme), Lionel FERRIERE (enseignant Histoire en collège et correspondant du musée de Romans), Michel MAZET (enseignant en lycée et correspondant des archives départementales).

Voir le bloc-notes

()

Voir le bloc-notes

()